Black and Transgender: The Art of Body Sovereignty Beyond Eurocentricity

‘Spirit attains its truth only by finding itself in absolute dismemberment’

—Achille Mbembe

When engaging with the strategic disenfranchisement of the black body how do we develop discourse and action that isn't driven by paranoia and isolation? How do we relent from a schizophrenia, instilled by both the necessity to progress and the enduring sexualization, de-sexualization, hyper masculinity and internalized fear of ourselves; relent from subversive pedagogies of how we should identify? And even, the nomenclature instilled by Western medicine in the first place? By the Atlantic in the first place, and by ourselves in the second? We speak of the necessity to excel, by and by tightly packaged in this idea of progression as capital, progression as policy and even progression as knowledge, deemed by the left. But who is going to teach us how to fly? Who is going to teach us how to see? Not with our eyes, not a worldview that is intrinsically Eurocentric, who is going to teach us insight? From where will we learn how to imagine, perform and grow beyond the postcolonial, beyond identity politics and into a realm of collective consciousness that actualizes the black body as Frantz Fanon puts it ‘in total fusion with the world’.

I remember the first time I saw my life experiences acknowledged on a public platform. I had encountered black queer people at meetups, in poetry circles, magazines, facebook groups and head nods on the train. And then, a few years ago, I bought a ticket to see the first showing of the film ‘Pariah’. I was excited to watch a film that at minimum included black queer characters and at maximum was familiar to my life. Yet what I was not prepared to see was the vernacular, social cues, social don’ts, religion, secrecy, fear, assertiveness, empowered vulnerability and struggle that is specific to the black community. When the lights turned on, more than half of the audience was wet faced with tears and overwhelmed by seeing themselves for the first time in mainstream media. And this year, we are at a pivotal point again, ‘Moonlight’ has won three Academy Awards, a Golden Globe and is succeeding in creatively mainstreaming black love.

But black love has always existed. Black queer, intersex and trans people have always existed. Their bodies, narratives and magic have always existed, beyond history. While accessing platforms of recognition is a positive stride towards removing ideas about ‘the other’, it is necessary that the strength of mapping narratives isn’t solely lost in the commodification of identities. We need not solely rely on a categorization and a homogenization of being in order to push policy that will take us further from the roots of aggression. While the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act was a step towards state protection, Trump legislation is quickly unraveling progressive policy (ie. withdrawal of bathroom rights for transgender students). And while the European Court of Human Rights declared transgender people are protected under Article 15 of the convention, the majority of black trans deaths are occurring in the Global South.

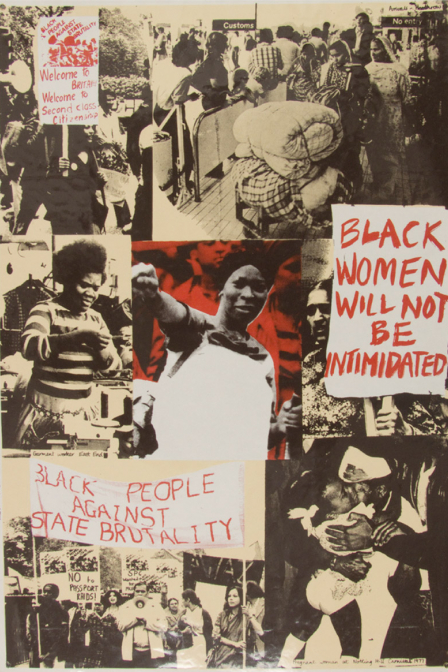

Black bodies, black trans bodies cannot progress in a system that was not built for them in the first place. In a system where blackness itself is deemed criminal and participation in a market economy, allows for comfortable complacency whilst black materialities are easily managed, distributed and disposed. ‘Positive visibility’ for black transgender people has become further embedded in valuing lives through policy based on death; and the convictions ‘achieved’ based on these policies are also furthering the prison industrial complex, ‘through which capital gains through the privatization of prisons’. And ultimately, ironically, black trans bodies are acting as resources for more privileged narratives and bodies to gain sovereignty. Intersectionality isn’t enough when growth is equivalent to victimhood, name-calling and continuously reproducing neoliberal ideologies.

While movements seek inclusiveness in deeply racist, sexist and normative societies, the fact that transgender people have always existed is being obscured. Memory has been constructed and replaced. Through the fashioning of the nation-state, representations of self, space and place are impacted by a wide range of discourse and perception. Universalism must be escaped in distinguishing between memory, which is sensory, transient and malleable and history which is fixed, written and enforced. For transgender people of African descent, progressive movement may lie in accessing the memories of their ancestors.

African cosmologies bear foundational similarities regardless of the borders instituted by the Berlin Conference of 1884. In Dahomean, Fon and Yoruba traditions, deities such as ‘Ayizan, Mawu-Lisa, Nanan-bouclou, Silibo-Gweto, Legba, Ayida Wedo, Damballah, Ezili, La Sirenn, Labalen, Ogou Sen Jak Maje, Ogou Ferraille, the Gedes, and the Barons Limba, Lundy, Oua Oua, and Samdi’ were all associated with gender and sexual diversity (Conner 2005). Legba and Mawu-Lisa in particular are conceived as ‘being transgender’ in modern terms. These deities amongst various others are not only still present in the socio-spiritual societies throughout particularly West Africa, Haiti and Brazil but continue to draw links between gender performance and pre-colonial African spiritualities.

In addition, researchers such as Professor Sekhmet Ra Em Kht Maat, are using ‘African worldview frameworks…to reinvigorate a continental and African diasporan collective consciousness through which Africana peoples can begin to define themselves and create their reality in relationship to the ordering patterns inherent within the universe’ (Maat 2012).

In Anu philosophy, the higher-self is offered as a facilitator of ‘oneness of being’ while the ‘material-social world is a reflection of the unconscious realm’ (Maat 2012). The concept of ‘Nu’ in this philosophy, is the starting point of creation which deems the body as having unlimited potential – while the concept of ‘Asar’, determining thought and behavior, recognizes a ‘non-gendered beingness’. With these concepts and an array of others, Maat offers the ‘Kemetic Model of the Cosmological Self’ to re-center African cosmologies when discussing gender, sexuality and performance. Often when people begin to identify as transgender, it is explained as a disconnection between conscious mind and physical body. Yet from this viewpoint, being transgender is a part of accessing one's consciousness and actively manifesting those qualities in the material realm. Rather than allowing ourselves to be positioned as outsiders that need to fight for inclusion, depending on the ideologies of the West to save us, memory could be actualized as a tool to shift consciousness and create social change.

The revitalization of precolonial memory allows for a re-imagination of the present. Currently, the greatest examples of this re-imagination take place through art. From Barry Jenkins to Toni Morrison, from Yinka Shonibare to Be Black Baby, from Wangechi Mutu to Poly Styrene. Art is the space where memory is realized, brought to life, and often only accessible in mobilizing ways by those that created it. Artwork like memory can piece together fragments of the past, transcending the enforcement of his-story.

To read and view more about how Khaleb Brooks links art to ancestral memory, visit their website.

Get it here