Dirty White Gold: The Seams of Sedition

Fashion, darling. There's no bigger canvas than fashion. It's the practical craft, design and form shown everyday on the everyman. Democratic in its pervasiveness, it's the one type of art that everyone owns. Preying on our very human sense of vanity, we use fashion to show the world what we'd like the world to think of ourselves. Looking good.

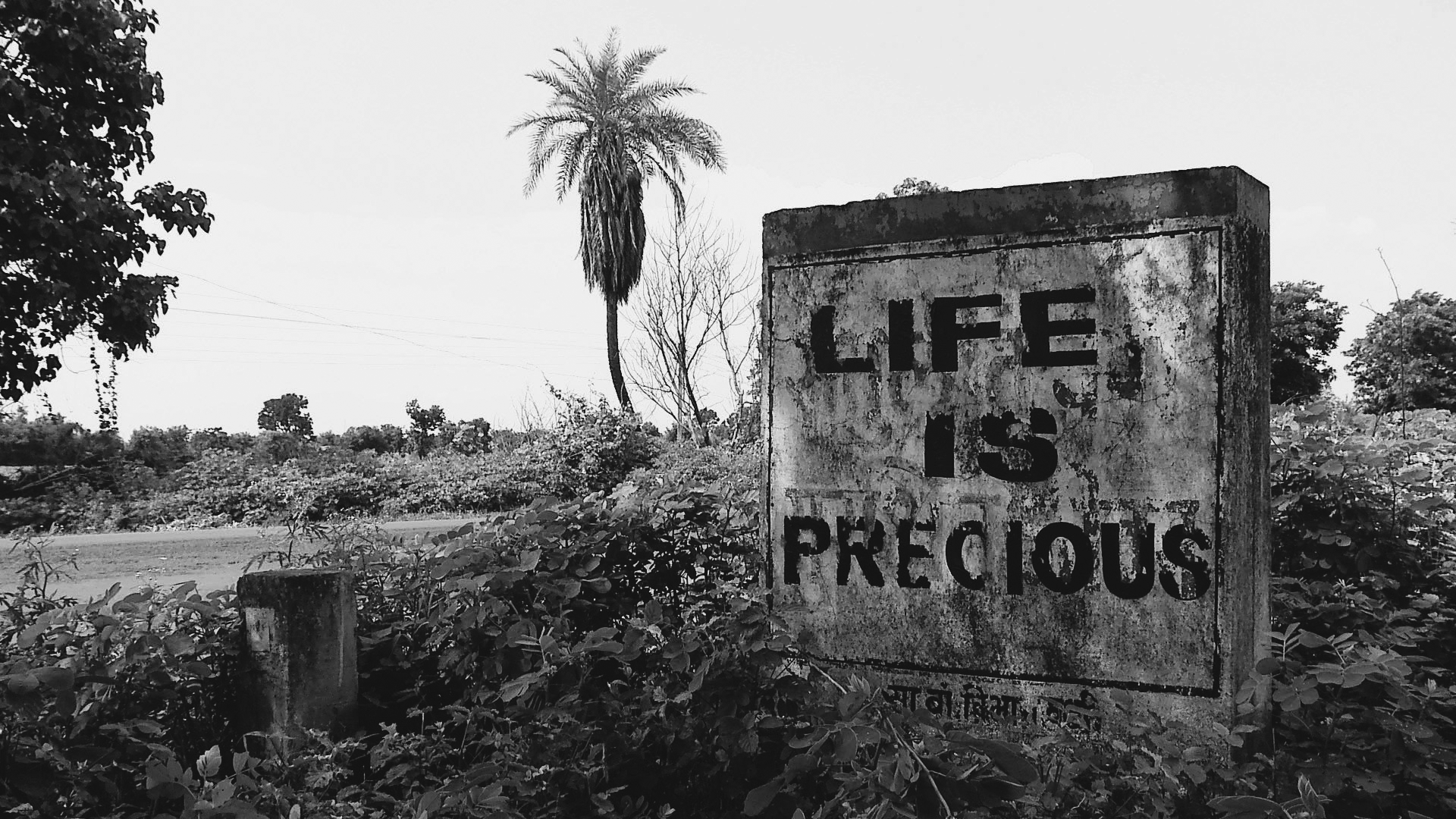

Or not. Nearly 300,000 Indian farmers have committed suicide to get out of debt since 1995. A great number of those farm cotton in a part of india called Vidarbha—otherwise known as the cotton suicide Belt. Much of that cotton ends up in the jeans we wear, the shirts we drape and the knickers we whip off.

Much like the way food we eat is packaged in a way that divorces us from the source of that food (have you eaten a burger lately?), the origin of clothes we wear is obscured by a complicated web of suppliers and middlemen that distances consumer from producer. The label says 100% cotton and made in Britain but what does it really mean?

I'm making a film that will unpick the fashion value chain. We'll ask: when you bag a bargain, who pays for it? is there room for ethics and sustainability in an industry that houses all the building blocks of capitalism and globalisation?

There is an estimated 80 billion new items of clothes made every year around the world. The global population hovers around 7 billion. Of that, 40 million of them are garment workers producing mainly fast fashion for the likes of H&M, Zara, Topshop and all the other places we're told to shop at if we want to keep ‘on trend’. These fast-fashion outlets produce knock-offs of couture and designer styles pushed on consumers by lifestyle magazines and advertising. Like the Diesel brand campaign For Successful Living, the language used to sell preys on self-image and the human need for acceptance and recognition. You might not have a lot of money, but you can buy a cheap item of clothing modeled on a style that looks like it cost a lot of money for about the same price as your lunch. Who cares if it won't last more than a handful of washes? You've been Facebooked wearing it so you obviously can't be seen in it again. The tragedy.

‘Looking good!’

‘Thank you.’

A spoil-sport somewhere will invariably ruin our consumerist fun by pointing out that what you're wearing was probably made by a factory worker in Bangladesh earning £35 a month. The sequins on your daughter's blouse were probably sewn on by a small child. Clothes made by kids, for kids.

Few spoil-sports go beyond the factory when they discuss supply chain transparency. The factory produces clothes that are cut out of fabric that is woven out of thread that is spun at a mill that gets raw cotton from a broker who's bought it from a farmer who has been paid less than the minimum price for toiling away in the fields for months. Current international rates put cotton at around fifty pence per pound.

The corporatisation of production and agriculture means there's little room for a fair division of wealth at the bottom end of the cotton supply chain. Hanuman, a farmer we met, borrowed around 80,000 rupees from the bank so he could grow cotton on his five acre farm. He'd spent almost the entire loan on boxes of BT [Bacillius Thuringienis] cotton seed and pesticides. The technology behind BT is owned by Monsanto and is licensed to seed companies for use and sale across a range of crops—it's meant to repel a pest known as the bollworm but does little to stop other pests. The seed our farmer uses costs 950 rupees a kilo. Monsanto gets around a quarter of this amount.

Global warming means the rains that feed his crops either fail or arrive late. The narrative among farmers is that organic farming offers lower yield and that brokers at the market pay the same price for organic cotton as they do for conventionally grown BT cotton. He's heard of the benefits of organic farming (lower costs, better health, etc.) but feels the risk of a lower yield is too much to take that gamble. Because last year's crop was less than satisfactory, he's borrowed more money to see if he can buy more seeds and chemicals to produce more this year. Rinse. Repeat. Welcome to the cycle of debt that drives farmers like Hanuman to drink the very pesticides they use to farm to kill themselves.

A common suggestion to ‘fix’ all this is to buy organic cotton. It's a start, but by no means a watertight solution. There are tight certification requirements that involve an economic hit the average small-scale farmer can't risk without proper support. At present, the market demands more than what organic farming can provide—especially when farmers are competing head-to-head with huge tracts of corporate farming carried out in America and China.

Here's where the activism comes in. Instead of accepting the things they can't change, some people are trying to change the things they cannot accept. Our film will take you on a journey from seed to shop—from fashion interns working for free to bolster an industry that's almost forgotten it's come out of art and expression, to the farmers toiling away so they can pay back the banks and loan sharks they've borrowed money from in order to eat. We're following the designers who incorporate ethics and sustainability into their clothes, the politicians fighting to debunk the idea that fashion is fickle feminine flu and the scientists and economists with the knowledge and skills to offer alternatives. We'll be poking into corporate sponsorship and green ini- tiatives and calling ‘bullshit’ on the biggest greenwashers.

To have a healthy and sustainable relationship with anything, you need trust and honesty. We're calling for transparency across the whole fashion supply chain. It's not an unreasonable demand. Just tell consumers where everything has come from and what impact that has on people and the environment. Bollocks to your ‘market sensitive information’. If a bunch of university students can take on the likes of Adidas and Nike and get them to behave better, think of what entire switched-on countries can do. Nobody likes being cheated on, and cheaters eventually get found out.

Get it here