Climate Change is Class War: Solidarity at the Coal Face

We’re in a pub in Hackney discussing why the messaging for Reclaim the Power—the direct action camp that took place in Balcombe this August—doesn’t have a ‘front-loaded’ climate message. My friend, a long term climate activist, is genuinely worried that the protest we’re organising, which at that point was going to be back at EDF’s West Burton gas power station, isn’t mobilising the key people we need to mobilise—climate activists—and that people don’t ‘get it’, and the whole thing isn’t ‘clear’. I try: We can’t ignore austerity. This is the time to join the dots.

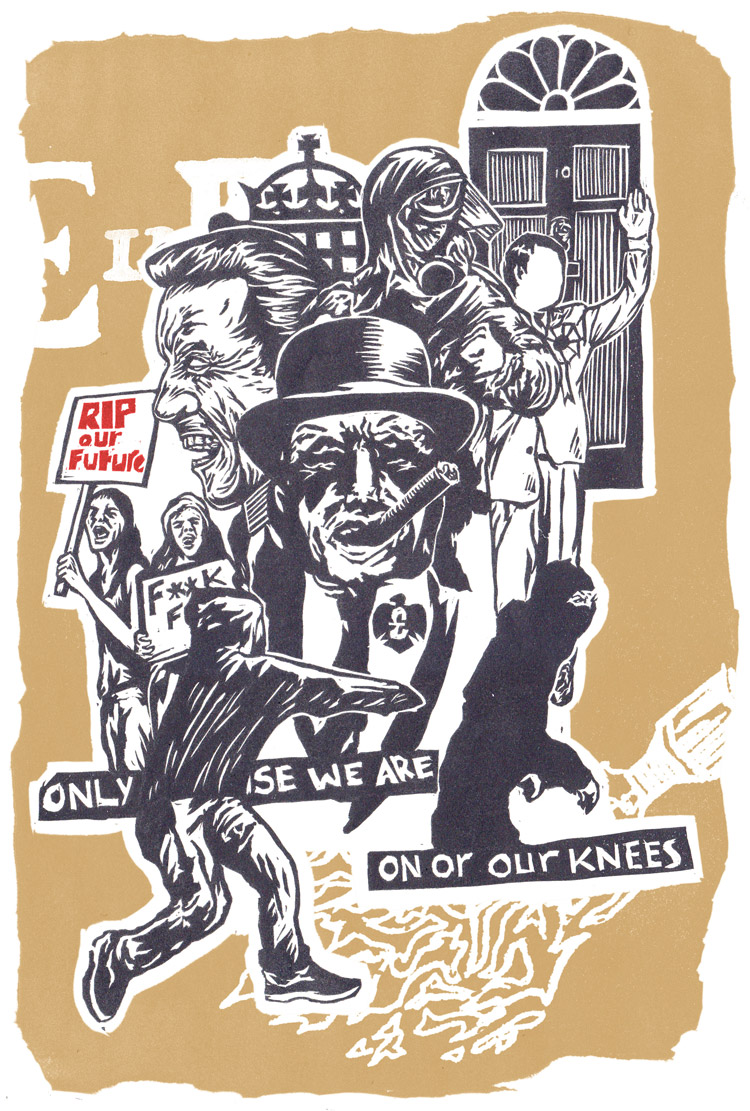

Right now it’s the Bedroom Tax, it’s cuts, it’s the NHS being sold off, it’s fuel poverty, it’s two years of the Tories and people are not waking up in the morning and thinking: Shit the icecaps are melting and we’re heading for climate catastrophe; they’re waking up and thinking: Shit I don’t know if I can pay the bills. We need to be able to respond to that. For too long, climate justice, struggles around energy democracy or how we reclaim a commons, haven’t had relevancy to the majority of people living in the UK. They’ve seemed external, an added dimension—even though they relate to everything. Climate Change isn’t getting people out onto the streets. If anything, it was Occupy and anti-capitalism-lite (Economic Justice) that got people out onto the streets in the last two years. The war on the poor, the reproduction of ‘the poor’, class war—this is what people are feeling now. ‘Class War?’ he says, he himself coming from a ‘benefits family’ way north in the isle, ‘but Climate Change IS class war’.

The economic crisis of 2008 has provided ruling elites around the world with a perfect alibi to continue restructuring, privatising and de-regulating public resources, institutions and spheres. And it is precisely these shock doses of austerity that are enabling bigger, longer-term shifts in policy and ownership to take place behind closed doors. One such shock-doctrine enabled policy is the UK’s ‘dash for gas’—the plan to build up to forty new Gas power stations, frack up to two thirds of England, and mortgage the UK’s energy future to the pollutant fossil fuel, controlled by Big Energy, for the next thirty years. Once these facts on the ground are established—a new extractive industry all over the country and massive power stations—they will be almost impossible to reverse. Beating Gas in the UK would open up the space for democratically controlled renewable energy to develop, on a localised basis. This wouldn’t automatically happen, but the space—political and economic—to make it possible would be opened up. Coal is over, nuclear would take too long: it is heading off gas that can bring us closer to Energy Democracy.

Everything for everyone

The Reclaim the Power coalition was a reflection of some of the climate, social and economic justice movements in the UK today: Occupy, No Dash for Gas, Fuel Poverty Action, Disabled People Against Cuts and UK Uncut. The idea behind putting this together was about showing that, to win, we need to co-operate and expose the systemic oppressions and structures that lie behind much of the disempowerment we’re facing. Look through the symptoms straight to the causes. It was the community in Balcombe, calling for solidarity to stop Cuadrilla drilling in their area, that changed the political game on climate in the UK this summer. We responded. Had RTP stayed at West Burton, we would have been ignoring a major debate-stirring, gas controversialising, democratic-deficit-exposing struggle on London’s doorstep. The decision to switch to Balcombe just one week before the camp showed the agility that a non-heirarchical network has when it needs to adapt and respond to new developments. Instead of taking action in an area where there was basically no resistance to the already established and running West Burton power station, we would be standing in solidarity with a community that actually did want us there, and where our arguments about democracy and the need to reclaim control over our futures would have far greater traction and resonance. We could also have a real impact on stopping a new fact on the ground from taking root.

The decision to move was compared to a previous decision to have a Climate Camp on Blackheath in 2011, targeting the financial sector rather than holding it in response to the Vestas workers’ occupation and struggle down on the Isle of Wight. The decision - set your own agenda or respond to an existing one, the former being the choice—was criticised by many at the time as lacking solidarity and being divorced from live social struggles.

Within hours of Reclaim the Power securing a site by squatting a field at Balcombe, despite heavy police presence, Cuadrilla announced that it would not drill for the entire duration of the camp—six days. We had a win and we hadn’t even started. This win was based on three factors:

Historical power

No Dash for Gas had achieved the longest power station shut down and occupation in UK history and beaten off EDF’s subsequent £5 million lawsuit, garnering huge public support and reputational damage to the French energy giant along the way. Cuadrilla had to wonder if this type of direct action could happen again? Direct action—by up to a thousand people—was the scariest-to-power element of the camp. The nature of the coalition and its reach—Occupy, UK Uncut, Disabled People Against Cuts and Fuel Poverty Action—also had a deterrent effect. Bar DPAC, all of these had already been defined as ‘terrorist threats’ in 2011 by City of London police.

An organised and established culture of resistance

RTP was based on the Climate Camp model of direct action, movement building and sustainable living that came from a culture of historical camps, including those of the anti-roads movement, Earth First gatherings, Greenham Common, traveller and free party sites and international anti-capitalist and No Border camps. It was amplifying and perpetuating a rich culture of resistance that had already succeeded in heading off the third runway at Heathrow (involving the support of a community-lead campaign in the village of Sipson) and new coal (Kingsnorth). This culture is one that sustains itself through an attempted ‘lived commons’—networks of low-cost housing co-operatives, squats and communal living, at times in direct confrontation to corporate interests; social centres; independent media and publishing co-ops; concrete tools and infrastructure that are shared and can be reused by groups (i.e. the Activist TAT Collective, which loans tents, water piping, toilets, and other essential infrastructure for camps); self-organised support networks focusing on legal defence, police monitoring and jail solidarity; medical care on actions; psychological trauma support; and further up from the grassroots, a fluid interplay between the political support of established NGOs and the physical support of members/workers who are often able to keep organising at the grassroots because they have financial sustainability and the time to research and build knowledge through working for an NGO. Add into this mix the funding from wealthy progressives: they’re often anonymous, but the cosmetic company Lush gave thousands to anti-fracking network Frack Off (who had been key in catalysing 45 local groups to fight fracking all over the country, and was a founding part of the existing Occupy-style camp at the road verges leading to the Cuadrilla site). All told, you have a network of networks based on a culture of trust, mutual understanding, confidence and participatory democracy that can effectively respond to capital’s evolving agendas.

Conflict Escalation Avoidance and neutralisation

Public opinion was already on the side of Balcombe locals: many sympathised with the conservative village and saw their plight as one of locals versus undemocratic big business and government policy. By neutralising the drilling, the company hoped to neutralise any participation and bridge-building between locals and the camp. If the aims of the camp had already been achieved—i.e. shut down Cuadrilla—then what was the point in travelling to Balcombe to protest? Our presence would be seen as ‘unreasonable’.

But the protests worked. Recent polling by the University of Nottingham showed support for shale gas extraction in the UK steadily rising for more than a year, peaking at 61% in favour in July, but falling to 55% by September. This is directly attributed to anti-fracking protests in the Summer.

Our climate, our commons

Reclaim the Power is not the only barometer by which to measure climate activism in the UK, but it does epitomise the coalition-building that is happening in order to generalise activism on reclaiming power for a commons - our climate, our energy, our labour. Focusing on a symptom of capitalism can open up genuine concepts of a collective and of what rights people should have to meet our common needs and aspirations. Drilling license applications in the UK could sow the seeds of a fertile network of resistance and coalitions dispersed all over the country. It can also provoke the possibility of planned alternatives—local sustainable community controlled power in your backyard rather than a fracking rig.

The movement is getting more diverse and class-orientated. Disaster capitalism is presenting us with the conditions for coalition-building and a form of disaster communism. Climate Change is Class war.

Get it here